Former DHS Secretary: US Should 'Seriously Consider' Hacking North Korean Weapon Systems

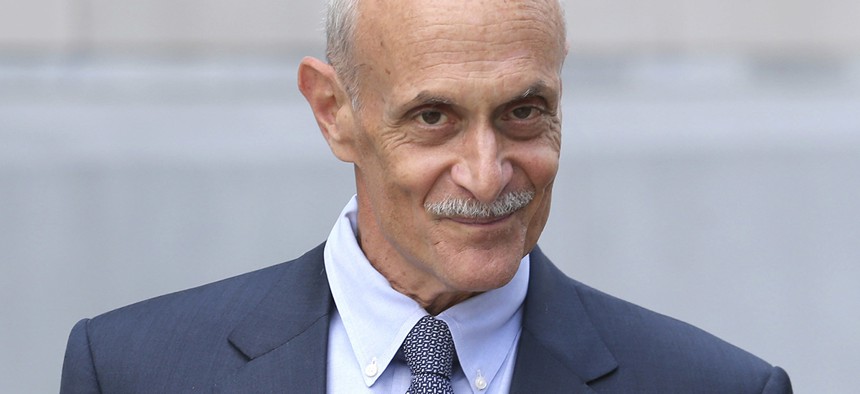

Former U.S. Homeland Security Secretary Michael Chertoff Seth Wenig/AP File Photo

When is it OK for the U.S. to hack another country?

The U.S. government should consider hacking North Korean information systems to thwart its nuclear ambitions, according to a former Homeland Security secretary.

Michael Chertoff, who headed the Homeland Security Department under President George W. Bush and now chairs the Chertoff Group, said the risk of North Korea attaining long-range nuclear capabilities poses enough of a threat to permit offensive hacking operations.

“As you look at what we see emanating out of North Korea—again, happily in the position of having no official role—I have sympathy for the view that any capability we have to delay or derail putting nuclear weapons in the hands of an unstable regime,” said Chertoff, speaking Tuesday at an event hosted by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

» Get the best federal technology news and ideas delivered right to your inbox. Sign up here.

“You’d have to seriously consider the appropriateness of that,” he added.

On Sunday, an attempted non-nuclear missile launch by North Korea failed, leading one former British foreign minister to suggest it might have been hampered by U.S. cyberattacks.

While the U.S. government has not weighed in on whether it has plans to engage North Korea in offensive cybersecurity missions, the proposition fueled debate regarding when it’s OK for governments to engage in such activity.

Spending estimates offer clues to how the U.S. government treats cybersecurity. For all the talk about cybersecurity keeping hackers out of U.S. systems, various reports say as much as 90 percent of the federal government’s cyber spend is on offensive capabilities, suggesting military and intelligence agencies are more aggressive in cyberspace than they let on.

In wartime, countries like Russia and China “talk openly about dominating” cyberspace, Chertoff said. In espionage, too, offensive intrusions are not uncommon among the world’s cyber powers. The U.S. was famously on the receiving end of a hack, attributed to China, of millions of security clearance records contained within the Office of Personnel Management’s systems.

“You’d be silly strategically not to consider tools in cyberspace to dominate the battlefield in war,” Chertoff said.

Less clear, however, are cases involving commercial espionage or the use offensive cyberattacks in peacetime. Publicly, the U.S. government loathes nation-states using their hacking capabilities to “achieve competitive advantage for [their] businesses,” Chertoff said, in large part because U.S. businesses lose billions of dollars annually in intellectual property.

Behind the scenes, it’s a different story, as detailed by recent media reports documenting how the National Security Agency allegedly infiltrated the Middle East’s banking system.

The U.S. has options in dealing with hacking nation-states other than hacking back, Christopher Painter, coordinator for cybersecurity issues at the State Department, said. These include sanctions, criminal indictments and diplomacy against transgressors.

In January, President Barack Obama imposed sanctions against Russia following its election interference, stating Russia carried out “significant malicious cyber-enabled activities.” In another example, Painter pointed toward the indictments of several hackers affiliated with Iran’s government for carrying out cyberattacks on a dam in New York and 46 financial institutions.

Finally, Painter detailed how diplomacy—visiting 25 different countries—helped bring about the end of a botnet army that had formerly had a presence in each. “We went to the countries formally and said, ‘Can you use what tools you have, can you help us mitigate this?’” Painter said. “It was a very positive experience.”

Yet, Painter added, there is no “silver bullet for doing this,” saying that any long-term stable environment in cyberspace must answer the question what is and isn’t acceptable from state actors.

Offensive cyberattacks should not be carried out on critical infrastructure that provide integral services to citizens, Painter said, nor should they be carried out on emergency responders amid disaster. Yet, for these and other possible “rules of the road,” Painter warned there will always be transgressors.