Why the US Still Can't Track Visitors Who Overstay Their Visas

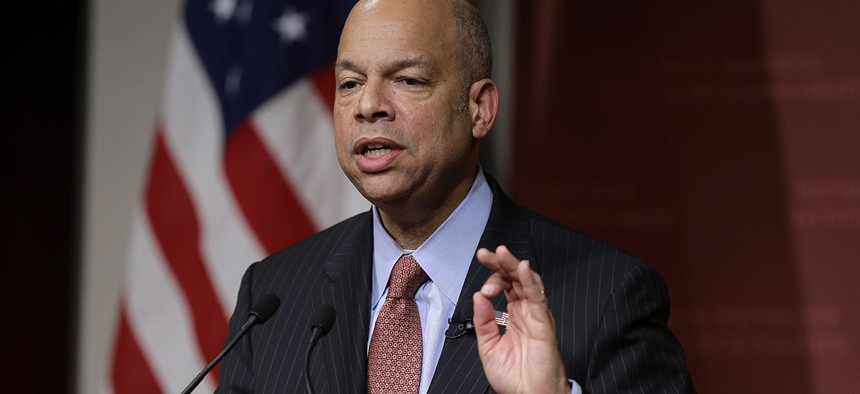

Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson Steven Senne/AP

Proposed “entry-exit” systems seem simple but have succumbed to real-world complications.

Wednesday night, Donald Trump attacked the Obama administration’s failure to enforce the law against people who overstay their visas.

“We must send the message that visa expiration dates will be strongly enforced,” he declared. But as with many of his promises, delivering won’t be easy. Although it’s a glaringly big security gap, both the Bush and Obama administrations have repeatedly tried and failed to overcome the hurdles necessary to plug it.

In early 2002, while I was researching my book on the aftermath of the Sept. 11 attacks, I sat in on a meeting in the vice president’s ornate conference room in the Eisenhower Executive Office Building next door to the White House. A group of senior executives from the giant defense contractor Raytheon, which had just formed a homeland security capture team, had arranged through a lobbyist-friend of Scooter Libby’s to make a presentation to former Secretary of Homeland Security Tom Ridge and his staff of what one of the Raytheon team promised as the meeting began was “a simple solution to one of your biggest problems.”

The problem was that millions of foreigners who are admitted on tourist or business visas for three to six months never leave. They just disappear into America. According to various estimates, these overstays make up a third to more than half of the 10 to 20 million illegal aliens in the country. That meant that solving the overstay problem was as important—or maybe more important—than building fences and hiring border-patrol agents to catch people sneaking in. In fact, five of the 19 Sept. 11 hijackers had been overstays.

So the Raytheon people had no trouble getting Ridge’s attention. What followed was a confident description of a big-data system that would record the biometrics of everyone with a visa (or people from the group of friendly countries, such as Great Britain or Canada, for whom the United States waives the visa requirement) entering at every airport, seaport, or land crossing.

The same biometrics would then be recorded when the foreigners left the country. If they did not leave on time, an alarm would go out to federal, state and local law enforcement officials across the country, who would check the names and even the biometrics of anyone they might stop for a traffic offense, for example, and thereby catch all the overstays.

In fact, other data-tracking technology could be used, the Raytheon people breezily promised, to snare the overstays if they used a credit card or otherwise had their names pop up in various transactions.

I couldn’t know it then, but when a half dozen of the Raytheon people had trouble firing up a laptop for their PowerPoint presentation, their failure to launch was a telling metaphor.

“That system sounds really complicated,” I remember asking one of the Raytheon people as we left. “How fast could you really get it going?”

“Well, we don’t have it yet, so we don’t know,” he replied. “But we know it’s out there.”

Congress, had, in fact, long assumed the same thing. Five years before 9/11, it passed legislation requiring the government to put this kind of “Entry-Exit” biometric identity-capture system in place by 2001. That was followed by renewed mandates after the attacks.

Each congressional directive, which had the force of law, resulted in promises by the government to get the system in place by deadlines that were never met, with each failure followed by an announcement of an entirely new initiative (requiring a new acronym).

The “entry” half of the program was, in fact, implemented beginning in 2006; everyone entering the U.S. now has their fingerprints taken. But the “exit” part has proved impossible to stand up because in the real world this kind of program isn’t nearly has “simple” as the Raytheon executive promised.

At the airports, where exit kiosks were initially tested, the airlines fought with the airport police who fought with homeland-security officials over who should maintain the machines and make passengers input their fingerprints. More significantly, vehicle crossings at the southern or northern land borders were not built to accommodate the exit kiosks, let alone deal with the slowdown in traffic if everyone had to leave a car or truck and get their fingerprints taken.

Similar complications stopped progress at the seaports. Even if the airport and seaport problems could be resolved, the inability to deal with the higher percentage of people exiting the U.S. over land whose exits could not be recorded would make any alarm system targeting those not reported to have left on time subject to false alarm rates of 50 percent or more. And, of course, we have done nothing to implement the back end of Raytheon’s plan—snaring overstays stopped by police or whose names pop up in commercial transactions.

So despite spending $600 million on failed pilot projects, there is still no Entry-Exit system. Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson told me he has promised Congress that “aspects” of the exit solution will begin being implemented by 2018.

However, DHS has finally met one congressional deadline associated with the overstay problem that has been mandated, and then renewed, almost annually since the mid-1990s. In January, just six months after its latest deadline, the department issued an official estimate of how many foreigners who entered the United States during the fiscal year ending Sept. 30, 2015, overstayed their visas: 527,000.