Seven Earth-Sized Planets Have Been Spotted Around a Nearby Star

NASA

And all of them are in the temperate zone.

In late 2015, in the Chilean desert, astronomers pointed a telescope at a faint, nearby star known as a red dwarf. Amid the star’s dim infrared glow, they spotted periodic dips, a telltale sign that something was passing in front of it, blocking its light every so often. Last summer, the astronomers concluded the mysterious dimming came from three Earth-sized planets—and that they were orbiting in the star’s temperate zone, where temperatures are not too hot, and not too cold, but just right for liquid water, and maybe even life.

This was an important find. Scientists for years had focused on stars like our sun in their search for potentially habitable planets outside our solar system. Red dwarfs, smaller and cooler than the sun, were thought to create inhospitable conditions. They’re also harder to see, detectable by infrared rather than visible light. But the astronomers aimed hundreds of hours worth of observations at this dwarf, known as TRAPPIST-1 anyway, using ground-based telescopes around the world and NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope.

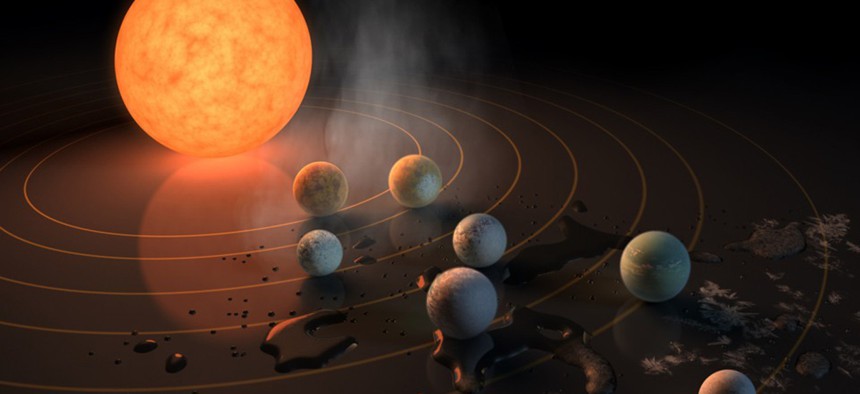

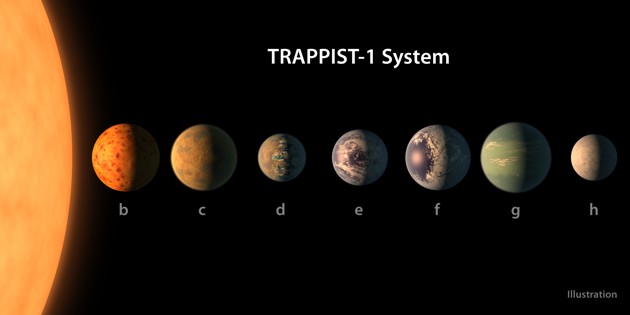

It paid off. There are not three, but seven rocky planets with Earth-like masses orbiting TRAPPIST-1, the astronomers reported Wednesday in the journal Nature. Even though it’s a star, TRAPPIST-1, located about 40 light-years from Earth, is only slightly bigger than Jupiter. If TRAPPIST-1 were the size of our sun, all seven planets would be well inside the orbit of Mercury. Despite the close quarters, the planets orbit in a part of the system where temperatures could be between 0 and 100 degrees Celsius, allowing liquid water to pool on their surfaces. Three of the planets are located firmly in the habitable zone, orbiting at a comfortable distance from the star, far enough to safely soak in the warmth without the heat vaporizing their atmospheres or boiling away water. The research, led by the University of Liège in Belgium, marks the largest bounty of Earth-sized planets ever discovered in a single star system.

Here’s an artist’s depiction of the seven planets:

The astronomers found the four newcomers by again measuring fluctuations in stellar light as the objects transited the parent star, revealing both their existence and information about their mass. Their findings suggest all seven are tidally locked, with one side perpetually facing TRAPPIST-1. (The habitable, water-friendly portion of each planet would likely be the ring between the hot, star-facing side and the cool, dark side.) The researchers estimate the orbital periods of the first six planets—the time they take to complete one loop around TRAPPIST-1—range between 1.5 and 12 days. The seventh planet made only one transit during the observations, so its orbit remains a mystery. The gravitational interactions between the six inner planets push them to orbit in a specific pattern around the star, a phenomenon known as a near-resonant chain. For example, for every eight orbits the innermost planet makes, the second makes exactly five. The system resembles Jupiter’s moons Ganymede, Europa, and Io, tidally locked objects that orbit in resonance, too.

TRAPPIST-1 and its septet of planets can’t be imaged directly, but that doesn’t matter much in the search for habitable planets. What’s needed is powerful telescopes capable of sweeping the system for biomarkers like oxygen and other exhalations of life. TRAPPIST-1 is a perfect target for star hunters like the James Webb Space Telescope, which in 2018 will begin scanning the skies from a vantage point of one million miles from Earth.

Until recently, red dwarfs were mostly overlooked in exoplanet exploration, but these ultracool stars seem to be proving skeptics wrong. Last August, astronomers using the European Southern Observatory in Chile discovered an Earth-sized planet orbiting in the temperate zone of Proxima Centauri, a red dwarf just four light-years away. In some ways their dimness is a boon for astronomers, as it makes it easier to see transiting objects and, potentially, signs of life on their surfaces. That’s good news, because red dwarfs are the most common kind of star in the Milky Way, accounting for more than three-fourths of the galaxy’s estimated 100 billion stars. There are likely many more systems like TRAPPIST-1, with plenty of Earth-sized planets.

The TRAPPIST-1 astronomers say they debated what a sunset may look on one of the tightly clustered planets. Despite its name, the red dwarf would emit a salmon hue, they decided, its darkest tones hidden in infrared, beyond the deepest red humans can see. The exoplanets could be frozen worlds, their icy crusts covered with cracks like the surface of Europa. Their terrain could carry the signs of water long gone, like channels carved by ancient floods on Mars. Or there could be water, lapping gently over rock beneath the salmon-colored sunset. And with luck, there might be something stirring underneath.